arstechnica.com | By Annalee Newitz | March 14, 2016

Artifacts found buried beneath village farms are rewriting British history.

Over the past month, our understanding of England’s distant past has been upended—not by trained archaeologists, but by two hobbyists with simple metal detectors. While prospecting in village farmlands, the two detectorists found clues that could change the way we understand Anglo-Saxon culture, as well as their battles against Viking invaders.

A seventh century island, hidden beneath farmland

Graham Vickers was prospecting in the farmlands of Little Carlton, a small village in Lincolnshire, when he discovered a silver stylus in a recently ploughed area. Styluses are ancient writing tools, designed to be used on wax tablets. Vickers quickly reported the finding to England’s Portable Antiquities Scheme, which brought in archaeologists from the University of Sheffield to explore the area. What they found changed their understanding of the region’s history—both in terms of human settlers and the natural landscape.

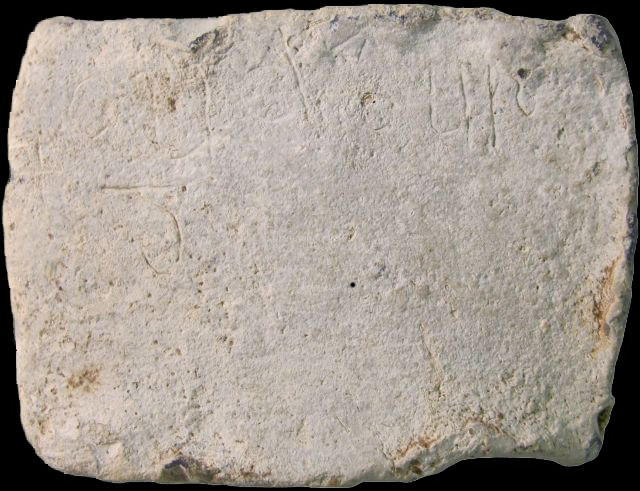

Eventually, archaeologists found a huge range of artifacts from the seventh and eighth centuries, including ornamental buttons and pins, 20 styluses, knives, coins, keys, imported German pottery, and even a gaming piece. One lead tablet was engraved with an Anglo-Saxon woman’s name, “Cudberg.”

Image courtesy of University of Sheffield

These objects are poignant hints at lives led by people whose history is largely unrecorded.Archaeologist Hugh Willmott told the BBC that the incredible range of items suggested a “high-status trading site,” or monastic center. “Far from being very isolated in the early medieval period, Lincolnshire was actually connected in a much wider world network, with trade spanning the whole of the North Sea.”

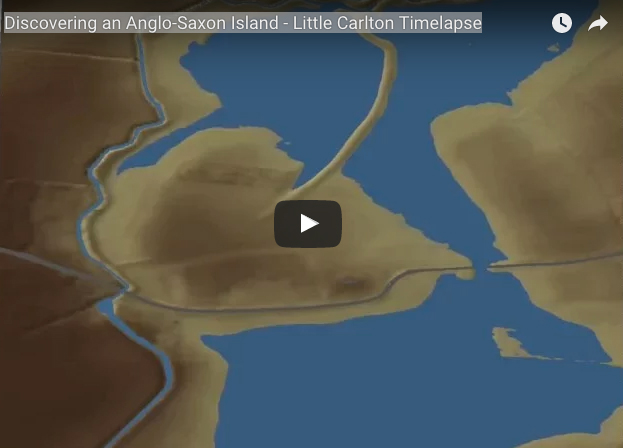

As scientists explored the site, it became obvious that its treasures could only be found in a very defined region—beyond the town’s edge, there were simply no more artifacts. What could have caused this? Was the town surrounded by a wall that had somehow disappeared? Using 3D modeling, Willmott and his colleagues solved the mystery. The town where Cudberg and her neighbors lived was, centuries ago, an island. During the eighth century, the area would have been much higher than the marshes and lakes surrounding it, reachable mostly by boat. This geographical feature probably also made it easy for locals to trade with merchants who sailed over from Europe.

Though historians know that England was colonized by Angles and Saxons during the sixth century, we know very little about their way of life at that time. There are scattered accounts, but most of what we know comes from Anglo-Saxon historians writing hundreds of years later. This discovery in Little Carlton expands our knowledge about that time dramatically, suggesting that the English coast was swarming with traders. The styluses are especially interesting, because they hint at a populace that was literate, sending written letters beyond the confines of their town—perhaps to other parts of England or to trading partners on the continent.

King Alfred’s secret ally

Roughly two centuries after a woman named Cudberg lost her metal stamp in the streets of an island town in Little Carlton, endless, dirty wars raged on the coast between Anglo-Saxon towns and Viking invaders. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a record of Anglo-Saxon history transcribed during the late ninth century, offers a depressing, year-by-year account of all the times the Vikings sacked English towns—or demanded gold to prevent the sacking, in an elaborate protection racket that went on for hundreds of years. But then King Alfred the Great rose to power in ninth-century Wessex, eventually defeating a Viking army at the famous Battle of Edington in 878.

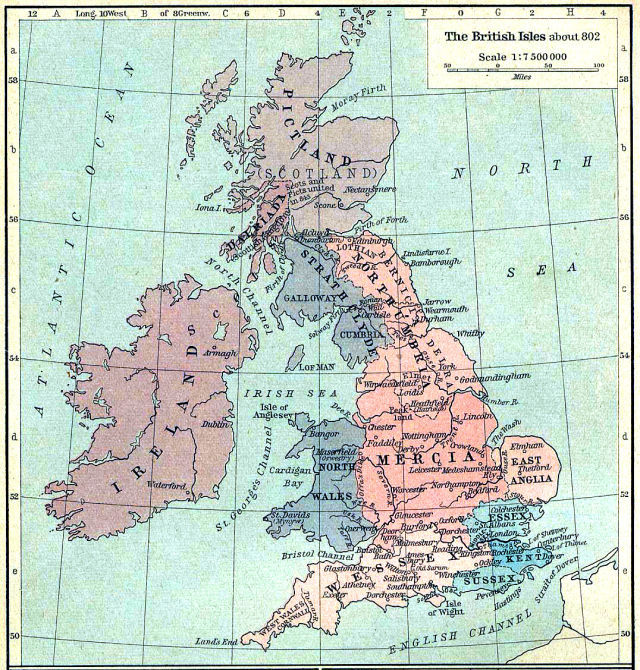

Alfred is often hailed as one of the first true kings of England, partly because he annexed the neighboring state of Mercia to create one of the biggest unified British kingdoms in history up to that point. He was also a Christianized leader who promoted literacy among his people, encouraging them to write in English as well as the more traditional Latin. It’s no accident that there’s a sudden outpouring of Anglo-Saxon writing during his reign and afterwards. During this era we get the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, followed by great works of early British literature like Beowulf and The Wanderer. People of the time wrote in a language that today we call Old English, which is closely related to German. Old English is almost unrecognizable to modern speakers, partly because English was completely transformed after the eleventh-century Norman conquest brought French into the language. That mixture of Old English and French resulted in the more familiar Middle English of Chaucer’s time.

Alfred wasn’t shy about using his people’s newfound literacy to spread propaganda, too. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes mention of a King Ceolwulf II, ruler of Mercia, who is described as a coward who sold out to the Vikings. Given that Alfred later annexed Mercia and put his pal Æthelred on the throne to rebuild the sacked city of London, it’s no surprise that he had nothing good to say about its former ruler.

But a new discovery in a farmer’s field reveals that perhaps Alfred’s relationship with Ceolwulf was more complicated than he let on. While prospecting in Watlington, Oxfordshire, James Mather found a silver slug that reminded him of Anglo-Saxon artifacts he’d seen in museums. After Mather shared his discovery with the Portable Antiquities Scheme, a team of archaeologists excavated a square chunk of ground from the site and brought the entire slab back to the British Museum for study. Cautiously, they chipped away at the thick hunk of clay, gently removing a buried treasure horde from a Viking settlement. All told, they found 186 coins, 15 silver ingots, 3 Viking-style arm bands, and several fragments of other kinds of jewelry.

Image courtesy of British Museum

During times of trouble, northern Europe residents often buried their valuables. That’s probably why these 186 coins were buried—it seems that this sack of coins and valuables was stashed roughly around the time that Alfred would have been beating back the Vikings at the Battle of Edington. It was a dangerous time to be a Viking settler in England.

What’s truly fascinating about the find, however, are the bits of history we can reconstruct from the coins. There are a number of coins bearing Ceolwulf’s face (see image at the top of this post), which makes it clear he was a much more powerful king than the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lets on (before now, archaeologists had found only one coin with his face on it). Plus, there are coins that show Alfred and Ceolwulf together, suggesting that the two formed an alliance to beat back the Vikings. “Poor Ceolwulf gets very bad press in Anglo-Saxon history, because the only accounts we have of his reign come from the latter part of Alfred’s reign,” said British Museum curator Gareth Williams during a press conference at the museum. “What we can now see emerging from his hoard is that this was a more sustained alliance with extensive coinage and lasting for some years.”

Though Alfred accused Ceolwulf of betraying him, these coins paint a more complicated picture. It may be that when Alfred’s alliance with Ceolwulf turned to bitter conquest, the great king rewrote history to suit his new role as unifier of Wessex and Mercia.

The discovery of this hoard and the lost Anglo-Saxon island of Little Carlton gives us tremendous insight into a historical period that has been buried—both accidentally, and in the case of Ceolwulf, deliberately. What’s remarkable is that we never would have discovered these treasures without the help of citizen scientists like Mather and Vickers. Their efforts are a reminder that history belongs to all of us and so does the scientific process.