SMARTNEWS Keeping you current

Smithsonian.com | June 28, 2016 | By Danny Lewis

Bone, tissue, and feathers show the almost 100-million-year-old wings are remarkably similar to those on modern birds.

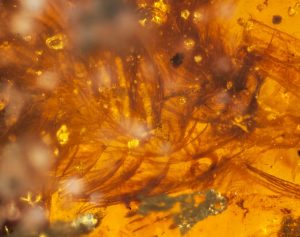

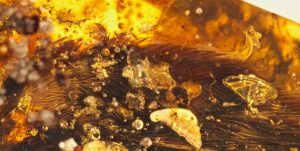

Finding things trapped in amber is far from a rare occurrence: lizards, bugs, flowers and more are regularly found encased in hardened lumps of the tree resin. But when a group of researchers digging through amber mined in Burma uncovered a sample with a pair of tiny bird-like wings frozen inside, they knew they had something special. At around 99 million years old, these wings are some of the most pristine fossilized feathers ever found.

“It gives us all the details we could hope for,” Ryan McKellar, curator of invertebrate paleontology at Canada’s Royal Saskatchewan Museum tells Sarah Kaplan for the Washington Post. “It’s the next best thing to having the animal in your hand.”

While birds and dinosaurs are related, the giant lizards didn’t directly evolve into modern birds. The first ancient birds began appearing during the Late Jurassic Period about 150 million years ago and then spent millions of years flapping in the shadows of their larger cousins. While scientists have uncovered many ancient bird fossils over the years, they are rarely very clear because their feathers and hollow bones don’t hold up nearly as well to the fossilization process as mammals, lizards, and the like, Kristin Romey reports for National Geographic. For the most part, researchers have had to make do with faint imprints of wings left behind in rock and amber.

“The biggest problem we face with feathers in amber is that we usually get small fragments or isolated feathers, and we’re never quite sure who produced [them],” McKellar tells Romey. “We don’t get something like this. It’s mind-blowingly cool.”

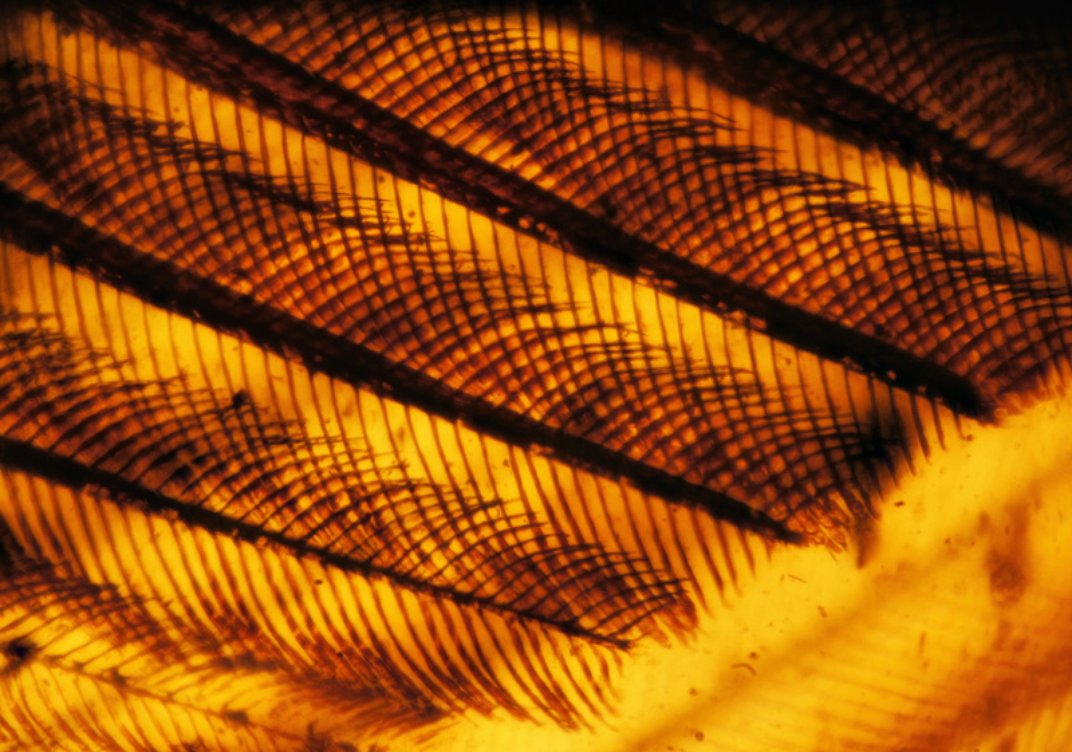

Astonishingly, the amber preserved every minute detail of the wings. If you look closely enough, you can see traces of hair, feathers, bones, and how they were all arranged. Even the feathers’ color has survived the eons and is still visible, George Dvorsky reports for Gizmodo. Using these little wings, McKellar and his colleagues can reconstruct what the birds might have looked like. They published their results this week in the journal Nature Communications.

By examining the feathers and wing remnants close-up, the scientists discovered that the bird was a prehistoric member of the group Enantiornithes. The tiny, hummingbird-sized animals were much closer in appearance to modern-day birds than their reptilian contemporaries, with only a few remaining vestiges of their scaly ancestors remaining, Kaplan writes. Though these ancient birds had teeth and and clawed wings, they otherwise looked very similar to most birds living today. However, they had one big difference: unlike most modern bird hatchlings, these creatures were born almost fully developed.

“They were coming out of the egg with feathers that looked like flight feathers, claws at the end of their wing,” McKellar tells Kaplan. “It basically implies they were able to function without their parents very early on…modern birds are lucky if they’re born with their eyes open.”

Even if the way birds develop has changed over millions of years, these fossils suggest that their feathers, at least, haven’t. The fossils spotted inside the amber indicate that their former owner’s plumage was very similar to that of modern birds. Though the world has changed dramatically since the time of the dinosaurs, it appears that birds are still flying using similar equipment as their ancestors.