BBC News US & Canada | By Daniel Nasaw | BBC News, Washington | August 2010

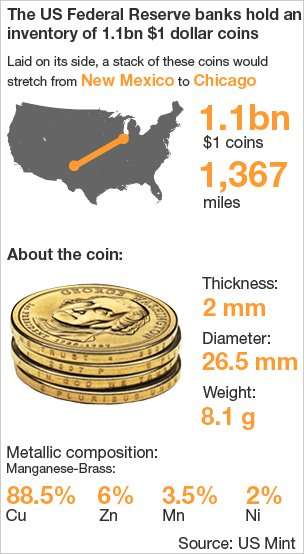

In hidden vaults across the country, the US government is building a stockpile of $1 coins. The hoard has topped $1.1bn – imagine a stack of coins reaching almost seven times higher than the International Space Station – and the piles have grown so large the US Federal Reserve is running out of storage space.

Americans won’t use the coins, preferring $1 notes. But the US keeps minting them anyway, and the Fed estimates it already has enough $1 coins to last the next 10 years.

And at the current rate, the inventory will grow to $2bn (£1.3bn) by 2016, the Fed estimates.

The coins began to pile up in 2007 when a law went into effect creating a new series of $1 coins commemorating dead US presidents.

Already stamped into millions of pieces of eight-gram, manganese-brass alloy are presidents no-one even remembers anymore, like Franklin Pierce, and ineffectual executives like James Buchanan, whose incompetence historians say helped lead the US to civil war.

‘Public resistance’

Congress passed the law creating the coins despite evidence that Americans never liked the $1 coin in the past.

Congress passed the law creating the coins despite evidence that Americans never liked the $1 coin in the past.

In a 2002 report, for instance, the investigative arm of Congress described “public resistance to begin using the dollar coin” despite a three-year, $67m (£42m) effort to promote the previous series.

Since the presidential coin programme began, the US government has spent an additional $30m to promote them but they still have not taken hold.

“We have tried every major idea that we can come up with, with limited success,” US Mint Director Edmund Moy told a congressional panel last month.

US officials say a peculiar set of factors have hindered public acceptance of the $1 coin.

“Americans are creatures of habit,” Mr Moy told Congress. “They are very used to using the bill. They’re not used to using coins in regular retail transactions.”

The US Mint has also identified an economic “awkward moment” in retail transactions involving the $1 coin. The buyer is afraid the cashier will reject the coin and cashiers are afraid buyers won’t accept them in change, so both are disinclined to try.

Mint and Fed officials have also identified a vicious cycle.

Retailers will not stock the coins because they do not see consumers using them, while consumers will not use the coins because retailers do not stock them.

Storage costs

Armoured car carriers and banks will not stock the coins until they are in greater use; banks still see the coins as collectors’ items, not money that consumers will use.

And even some coin collectors dislike them.

“We’ve had any number of people over the years complain about receiving a dollar coin,” says Tom DeLorey, a Chicago coin dealer.

Yet the piles have continued to grow because the law requires the US Mint to issue four new presidential coins each year even if most of the previous year’s coins remain in government vaults.

In addition to the millions spent to promote the coins, shipping, storing and guarding the excess inventory costs money, though how much is unclear.

Congressman Melvin Watt, a North Carolina Democrat who chairs a subcommittee with jurisdiction on the issue, said Mint and Fed officials had yet to respond to his requests for a detailed accounting.

The US Mint declined to make officials available for an interview.

The Fed has warned Congress of rising storage costs but declined to provide detailed figures to the BBC.

Replacing paper money

US officials and coin experts note that Australia, Britain, Canada and Japan have successfully introduced coins in similar denominations, but only after phasing out paper notes.

Most countries in the G8 have ceased to circulate a note in their base unit of currency.

Because a coin can last four decades while a note lasts only a few years, replacing the dollar bill with the coin could save the US $500m to $700m per year in printing and paper costs.

Only an act of Congress could slow or halt the coins’ pile-up, either by phasing out the $1 note or halting the minting of the coins. Neither is likely to happen soon in today’s polarised, bitterly partisan political environment, though some in Congress are clearly frustrated.

“We shouldn’t continue to push a coin that isn’t going anywhere,” Mr Watt tells the BBC.

No legislation has been introduced to remedy the problem, though Mr Watt says he anticipates taking action next year.

At least one congressman has called for legislation to phase out the $1 note, noting the declining purchasing power of a single dollar.

“I don’t see why we need to have the federal government go through the expense of making and replacing paper money for an amount of value that has traditionally in this country been represented by a coin,” Congressman Brad Sherman, a California Democrat, said last month.

Until the US phases out the $1 note or stops minting the coins, they will keep piling up in the vaults.

“People will grumble and [the coins] will be unpopular for a few months but then they’ll get used to it,” says David Lange, director of research for the Numismatic Guaranty Corporation, a service for coin collectors.

“It’s that simple.”

Or, in the bureaucratic language of Congress’ investigative arm: “The most substantial barrier is the current widespread use of the dollar bill in everyday transactions.”