By Jonathan Ball | BBC News – Science & Enviornment | August 12, 2012

Some of the earliest fossils of pre-historic arthropods – dating to about 230 million years ago – have been discovered entombed in amber, PNAS journal reports.

Arthropods – a highly diverse family of invertebrates, which includes insects, arachnids and crustacea – constitute more than 90% of the entire species within the animal kingdom.

The previous earliest records of arthropod-containing amber dated back to the Cretaceous period, around 135 million years ago.

The researchers hope that the recent find – of two plant-feeding mites and one insect – will provide important insight into the early evolution of this highly diverse family of animals.

Amber is fossilised plant resin. The resin often entraps plant and animal material which then become buried – as “inclusions” – when the fossil amber forms.

A key feature of amber is its ability to preserve key features – such as the soft body parts – of the inclusions. It has become an important aid to understanding the early evolution of life.

As Prof. David Grimaldi from the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and lead author of the study, explained: “Amber is an extremely valuable tool for palaeontologists because it preserves specimens with microscopic fidelity, allowing uniquely accurate estimates of the amount of evolutionary change over millions of years.”

The previous earliest arthropod-containing specimens of amber formed during the Cretaceous period – 145 to 65 million years ago (Ma).

Dr. David Penney – an expert fossil researcher from the University of Manchester – told BBC News: “Many new Cretaceous amber outcrops rich in arthropods have been found over the last decade and these have increased our knowledge [of these important creatures].”

Experts have now turned their attention to amber from even earlier periods of the Earth’s geological past.

What mite have been

According to Dr Penney: “A couple of tantalising possibilities have presented themselves in recent years including several new Jurassic outcrops in Lebanon. But as yet, no inclusions have been found.”

In the current study, Prof. Grimaldi and his team analysed amber deposits recovered from outcrops near to the village of Cortina in the Dolomite Alps of north eastern Italy.

These measured just a few millimetres across and were formed in the late Carnian stage of the Triassic period, around 230 Ma.

The deposits were excavated by Prof. Eugenio Ragazzi and Prof. Guido Roghi of the University of Padova, who had previously described the presence of microorganisms in Triassic amber formations.

As Dr. Penney explained, “There has been excitement around finding pre-Cretaceous ambers with arthropod inclusions for some time”.

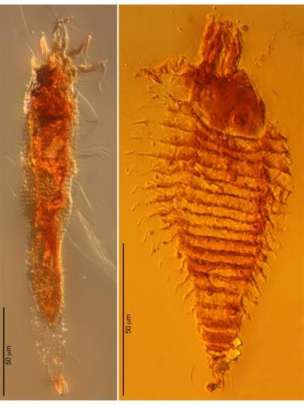

After a painstaking screen of more than 70,000 droplets, Prof. Grimaldi and his team discovered three ancient arthropods – including two species of previously undiscovered mite – entombed within these small resinous gems.

The new mite species are the oldest fossils of an extremely specialised group called Eriophyoidea. This contains about 3,500 living species, all of which feed on plants and sometimes form abnormal growth called “galls”.

The ancient mites most likely fed on the leaves of an extinct conifer tree that ultimately preserved them.

Commenting on the evolutionary adaptability of the mites Prof. Grimaldi said: “We now know that gall mites are very adaptable.

“When flowering plants entered the scene, these mites shifted their feeding habits, and today, only 3 percent of the species live on conifers. This shows how gall mites tracked plants in time and evolved with their hosts.”

Despite this adaptability the appearance of the mites has changed very little over the years.

As Prof. Grimaldi observed: “You would think that by going back to the Triassic you’d find a transitional form of gall mite, but no.

“Even 230 million years ago, all of the distinguishing features of this family were there – a long, segmented body; only two pairs of legs instead of the usual four found in mites; unique feather claws, and mouthparts.”

Dr. Penney was surprised by the find: “The results presented here skip the Jurassic entirely and go back a step further to the Triassic. This was not expected.”

On possible future discoveries and their importance he added, “It is a shame that future finds are expected to be in such a small size class due to the limitations of the amber recovery.

“Nonetheless, as the authors point out, future discoveries have great potential for understanding the early evolution of some groups as the Triassic Period follows a major extinction event.”