BBC NEWS Science & Enviornment | November 20, 2013

Scientists have mapped the genome of a four-year-old boy who died in south-central Siberia 24,000 years ago.

It is the oldest modern human genome sequenced to date, researchers report in the journal Nature.

The results provide a window into the origins of Native Americans, whose ancestors crossed from Siberia into the New World during the last Ice Age.

They suggest about a third of Native American ancestry came from an ancient population related to Europeans.

Analyzing the genes of present-day populations can only tell us so much about the past because traces of ancient movements have been overwritten many times.

So studying the DNA from ancient remains is becoming a powerful tool for disentangling the numerous waves of migration that produced the genetic patterns seen in people today.

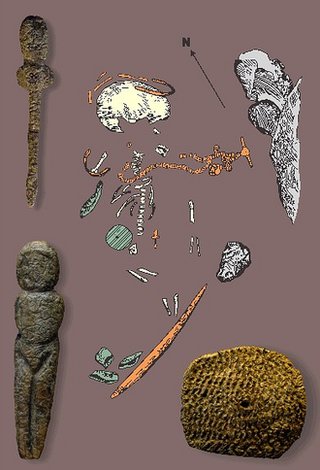

The burial of an Upper Palaeolithic Siberian boy was discovered along with numerous artifacts in the 1920s by Russian archaeologists near the village of Mal’ta, along the Belaya river.

“With these remains of a young kid were all sorts of cultural items, one of which was a Venus figurine,” lead researcher Eske Willerslev, from the University of Copenhagen, told the Nature podcast.

“These Venus figurines are found all the way west of this area into Europe.”

Dr. Willerslev and a colleague obtained a sample from the boy’s arm bone, extracted DNA and compared it with that of present-day populations.

“When we sequenced this genome, something strange appeared,” he explained. “Parts of the genome you find today in western Eurasians, other parts of the genome you find today in Native Americans – and are unique today to Native Americans.”

DNA from the boy’s Y chromosome and from the mitochondria (the cell’s batteries) were of types found today in a region encompassing Europe, West and South Asia and North Africa, but rare or absent in Central Asia, East Asia and the Americas.

The researchers estimate that 14-38% of the ancestry of Native Americans traces to a population like the one living at Mal’ta 24,000 years ago.

But the most puzzling part of this finding was that the boy showed no clear affinities with East Asian populations such as the Chinese, Koreans or Japanese.

Today’s Native Americans are most closely related to East Asians, so the scientists had to work out how the Mal’ta boy could be related to indigenous Americans, but not to East Asians.

The most likely scenario, they argue, is that a population like the one living in Siberia 24,000 years ago mixed with the ancestors of East Asians at some point after the boy died.

“Native Americans are composed of the meeting of two populations – an East Asian group and these Mal’ta west Eurasian populations,” said Dr Willerslev. However, it remains unclear where this mixing took place.

“It could have happened in the Old World, somewhere in Siberia obviously. Or, in principle, it could also have happened in the New World,” he explained.

“The most direct way to address this question would be to genome sequence some of the early skeletons from the Americas. If they already have the mixture of East Asians and the Mal’ta then we know it happened before that.”

The research could help explain some long-standing anomalies in the study of Native American origins.

For example, some early American skeletons – such as the 9,000-year-old Kennewick Man from Washington State – bear physical features that, according to some, are typical of Europeans, and unlike those of modern Native American groups or East Asians.