BBC News Europe | By Giorgos Christides | Amphipolis, Greece | September 22, 2014

The discovery of an enormous tomb in northern Greece, dating to the time of Alexander the Great of Macedonia, has enthused Greeks, distracting them from a dire economic crisis.

Who, they are asking, is buried within.

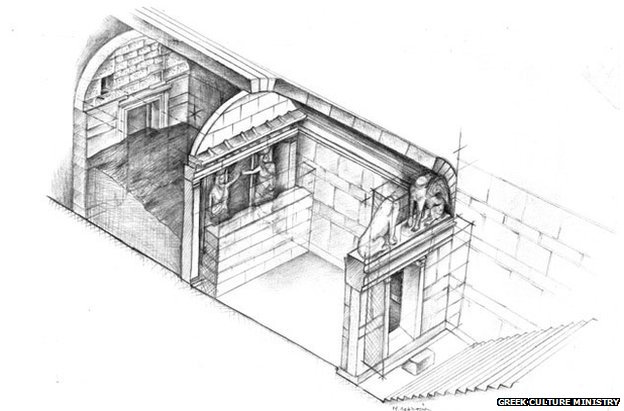

In early August, a team of Greek archaeologists led by Katerina Peristeri unearthed what officials say is the largest burial site ever to be discovered in the country. The mound is in ancient Amphipolis, a major city of the Macedonian kingdom, 100km (62 miles) east of Thessaloniki, Greece’s second city.

The structure dates back to the late 4th Century BC and the wall surrounding it is 500m (1,600ft) in circumference, dwarfing the burial site of Alexander’s father, Philip II, in Vergina, west of Thessaloniki.

“We are watching in awe and with deep emotion the excavation in Amphipolis,” Greek Culture Minister Konstantinos Tasoulas told the BBC.

“This is a burial monument of unique dimensions and impressive artistic mastery. The most beautiful secrets are hidden right underneath our feet.”

Ancient and modern guardians

whereas the eastern caryatid’s face is missing

Inside the tomb, archaeologists discovered two magnificent caryatids. Each of the sculpted female figures has one arm outstretched, presumably to discourage intruders from entering the tomb’s main chamber.

The caryatids’ modern counterparts are sitting in a police car, some 200m (650 feet) from the tomb’s entrance.

The dig site is protected 24 hours a day by two police officers.

Their mission is to keep away the scores of journalists and tourists who arrive here by a winding dirt road from the nearby village of Mesolakkia.

An imposing no-entry traffic sign serves the same purpose.

Amphipolis site

• 437 BC Founded by Athenians near gold and silver mines of Pangaion hills

• 357 BC Conquered by Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great’s father

• Under Alexander, served as major naval base, from which fleet sailed for Asia

• 1964 First official excavation began, led by Dimitris Lazaridis

The excavation team has made no statement regarding the identity of the tomb’s occupant.

But this has not prevented the media, archaeologists and laypersons alike from becoming embroiled in an often heated guessing game.

Archaeologists agree that the magnificence of the tomb means it was built for a prominent person – perhaps a member of Alexander’s immediate family; maybe his mother, Olympias, or his wife, Roxana -or some noble Macedonian.

Others say it could be a cenotaph.

But only the excavation team can give definitive answers, and progress has been slow since the workers discovered a third chamber that is in danger of collapse.

Experts have not reached a verdict, but for the few hundred inhabitants of modern-day Amfipoli and Mesolakkia, the two villages closest to the burial site, there is no doubt: interred inside the marble-walled tomb unearthed near their homes is none other than Alexander the Great.

“Only Alexander merits such a monument,” says farmer Antonis Papadopoulos, 61, as he enjoys his morning coffee with fellow villagers in a taverna opposite the Amfipoli archaeological museum.

“The magnitude and opulence of this tomb is unique. Common sense says he is the one buried inside.”

Archaeologists and the Greek ministry of culture warn against such speculation, especially since Alexander the Great is known to have been buried in Egypt.

“We are naturally eager to learn the identity of the tomb’s resident, but this will be revealed in due course by the excavators,” Mr Tasoulas, the culture minister, says.

Alexander the Great

• Born 356 BC in Pella, son of Philip of Macedon and Olympias, educated by Aristotle hills

• Became king of ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon at age 20

• Military victories in Persian territories of Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt – “great king” of Persia at 25

• Founded 70 cities and empire as far east as the Indian Punjab

• Died 323 BC of fever in Babylon

The discovery, made after two years of digging, was announced during a visit to the site last month by Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, who described it as “very important”.

Since that announcement, Amfipoli and Mesolakkia have been teeming with people, who have disturbed the slow rhythms and tranquillity of village life.

“Journalists and visitors suddenly started pouring in from all over Greece and abroad. We used to walk by the site every day, working the fields. We knew something was there, but we did not expect the magnitude of this discovery,” says Athanasios Zournatzis, head of Mesolakkia’s community.

A Belgian couple from Liege pass by and tell me they came to visit after reading about the tomb in the newspaper at home.

The discovery has given rise to a wave of Greek pride and patriotism, and has helped the nation put its economic predicament to one side – temporarily at least.

• Amfipoli resident Giorgos Bikos believes news of the tomb “has thrown Greeks a lifeline”

• Leading daily Kathimerini suggested people were naturally looking for good news amid a “constant barrage of doom and gloom”

• Culture Minister Mr Tasoulas says it is a reminder that Greece is the “cradle of an unsurpassed civilisation and a country that deserves, with this unique [cultural] capital and its present-day accomplishments, to claim its return to progress and prosperity”

The residents of Amfipoli and Mesolakkia are hoping this feel-good factor will last long enough to make their villages tourist attractions and give them a much-needed economic boost.

At Mesolakkia, the meeting point of visitors and journalists is a traditional kafenio, or cafe, with a dominating platanus tree providing protection from the warm September sun.

Mr Zournatzis says the villagers are “hoping they have won the lottery”.

Father Konstantinos, a 92-year-old priest, says he is following developments and “shares the excitement”.

Villagers say they have already been approached with offers to sell their land. Most could use the money, but they are holding off until archaeologists make an official announcement.

“Before the discovery, land here was worth close to nothing. But now no one is selling,” says Mesolakkia resident Menia Kyriakou.

A group of six women drinking their morning coffee at a nearby table explain that following latest developments is not straightforward.

Balkan Studies graduate Eleni Tzimoka, who recently moved back to the village from Thessaloniki, says they are waiting at the cafe for the phone company to install an internet connection.

“We know the tomb story is big, but without access to the web, it is hard to keep up.”