The Huffington Post | By Meredith Bennett-Smith Posted: 07/15/2013

Watch Video

The ability to track time may have been available thousands of years earlier than previously thought, according to researchers in Scotland who have discovered what appears to be a 10,000-year-old “calendar.”

Archaeologists from the University of Birmingham recently announced the results of their analysis of a series of 12 pits dug in a field in Aberdeenshire in the journal Internet Archaeology. The discovery is believed to date back to about 8,000 B.C.

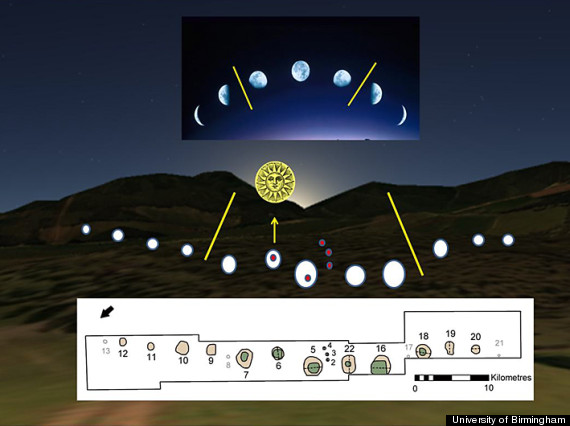

The Mesolithic monument — part of the Warren Field site originally excavated in 2004 — appears to mimic the phases of the moon and may have been used to track the lunar months.

Laid out in an arc, the row of pits is 50 meters (about 164 feet) long, according to the Scotsman. The pits, which alternate in depth, represent what could have been a fairly sophisticated measuring system, splitting the lunar month into three ten-day weeks.

“The evidence suggests that hunter gatherer societies in Scotland had both the need and sophistication to track time across the years, to correct for seasonal drift of the lunar year and that this occurred nearly 5,000 years before the first formal calendars known in the Near East,” Vince Gaffney, project leader and University of Birmingham landscape archaeology professor, said in a University of Birmingham press release. “In doing so, this illustrates one important step towards the formal construction of time and therefore history itself.”

Researchers were quick to stress the anthropological importance of the find.

“The capacity to [conceptualize] and measure time is amongst the most important achievements of human societies, and the issue of when time was ‘created’ by humankind is critical in understanding how society has developed,” the journal article’s summary notes.

The lunar calendar would have had major cultural and economic implications for the hunter-gatherers living in the area, National Geographic reports.

“It shows that Stone Age society was far more sophisticated than we have previously believed, particularly up north, which until lately has been kind of a blank page for us,” said Richard Bates, a geophysicist from University of St. Andrews who worked on the project.

Read more at Huff Post World